Still Here

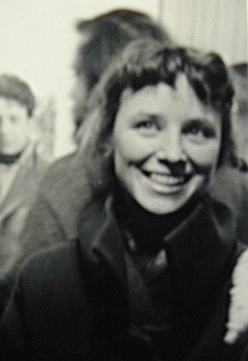

/Dick Bellamy, Provincetown, 1957, photo by Ivan Karp

Since Eye of the Sixties came out, I have been thinking about the village of support I had when writing my book . Some of the artists, art world players and assorted loved ones, relatives, colleagues and peers of Richard Bellamy I interviewed in the last two decades have passed away, but happily, many more are still very much here. On September 14, I was on stage at the New York Public Library with four such people who were key to my work as a biographer. Many thanks to Clocktower Gallery for creating this podcast of the event.

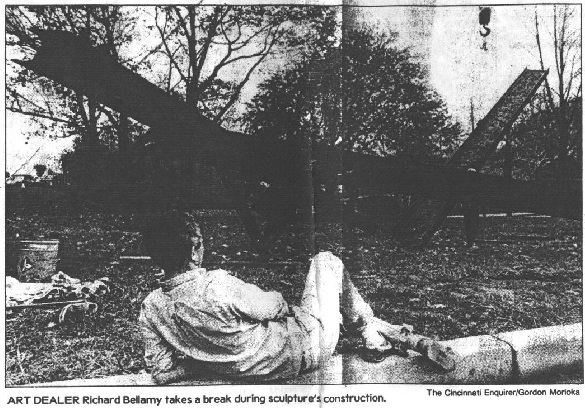

Mark di Suvero made his debut as a sculptor in 1960 as the first show Dick Bellamy mounted at his Green Gallery. Dick became Mark’s first, and for many years, his only dealer. I remember talking about Dick with Carl Soloway, the late Cincinnati art dealer who dedicated himself to the career of Nam June Paik, the founder of video art. Soloway laughed when he described both himself and Dickas “monogamous dealers,” referring to his lifelong support of Mark’s art. When thinking out loud about Dick as part of the library panel, Mark’s heartfelt emotions were moving to many in the audience (including me).

Dick liked to refer to himself as “a gentleman of the old school,” which meant in part that when he believed in an artist, he stayed loyal for life. He first saw Alfred Leslie’s work in the fifties when the painter was an internationally-recognized abstract expressionist, although he himself started showing Alfred’s work in the sixties when he’d moved on to figurative painting. On the panel, Alfred too spoke movingly about Dick, his friend and dealer. Alfred is in his late eighties and continues to be a self-described “octopusarian.” At The Toast is Burning, his current show at Bruce Silverstein (through November 12), he’s exhibiting iconic, large-scale portraits from the 1960s, and new pigment prints. But you have to visit his website to see his graphic novels.

Richard Nonas got to know Dick in the seventies, and his was the first show in Dick’s Oil & Steel Gallery in 1980. He pointed out that Dick was not interested in art as commodity, and saw art as an affirmation of what makes us human.

Another of the speakers was Miles Bellamy, Dick’s son and author of Serious Bidness, a wonderful new collection of Dick’s letters. Miles worked with Dick in the nineties and has become an essential part of New York’s literary scene, with two Spoonbill & Sugartown bookshops in Brooklyn (Serious Bidness available here online or on foot).

Among those in the audience was Jonathan Scull, son of collectors Ethel and Robert Scull — pivotal players in the 60s and 70s art world and secret backers of Dick Bellamy’s Green Gallery — who owns Scull Communications, a PR firm specializing in the electronics industry. Jonathan also was essential to my book, and over the years I interviewed him several times. I caught up with him a few weeks later at a party for Eye of the Sixties. It wasn’t easy growing up with Bob and Ethel as parents, he revealed, yet he’s finding, to his surprise, that much of what has made him successful in business he learned from his father.

I will continue providing updates on the large web of connections to Dick Bellamy that reverberate around the world. If you would like to contribute your own, this Facebook site dedicated to Dick is an ideal place to share them. I welcome them, too.